When Sharon Rose Kootenay began work on an outdoor installation commissioned in 2020 by The Works Art & Design Festival, she feared it would be the last piece of art she would ever make.

A self-taught Métis Cree Heritage artist with deep roots in traditional women’s practices, Kootenay often worked with animal hides in enclosed spaces while meeting tight deadlines. “When you use commercial leather, the processes are very harsh; the manufacturers use formaldehyde, arsenic and all these terrible chemicals,” she says. “My vocal cords shut down and I couldn’t breathe.”

Just as her health collapsed, grim news of the pandemic and racial tensions filled the airwaves. Far from being ground down, Kootenay was determined to channel her grief into something beautiful.

“If it was going to be my last piece, let it be meaningful,” she said, and named the piece Transformation: Promise and Wisdom.

Working in collaboration with her former photography instructor, Jason Symington, they set out to design the Giant Gateway — an entranceway to The Works Festival grounds in Churchill Square — so it would comfort people in the darkest days of winter.

On the gateway’s pink side, blossoms and vines rise up to the sky, reassuring us that things will get better. “It’s an interpretation of the Creator’s promise,” says Kootenay. “The turning of the seasons brings new life; it will bring happiness again.”

On the blue side, vines reach down, evoking wisdom. “In Cree/Métis spiritual practices, we believe that grandfathers and grandmothers are always with us, they are departed spirits who watch over us,” says Kootenay. “During COVID, if people were upset, they should know that there is a presence that’s guiding them and they aren’t to worry.”

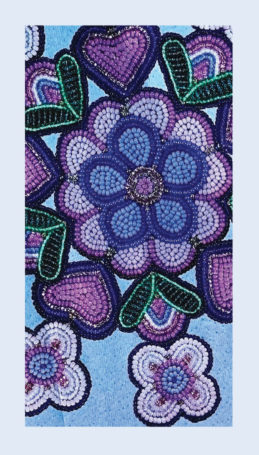

The original flowers, photographed and enlarged for the archway, were located just a few blocks away in another Works Festival show, entitled Wildflowers: Métis Women of Fort Edmonton, 1785 – 1910. It featured Kootenay’s beaded and meticulously crafted birch-bark baskets, women’s belts and other items inspired by handicrafts of eight Métis/Bois-Brûlé women who were essential to the early settlement of Fort Edmonton.

These works — among Kootenay’s decades-long body of artwork that began as she was too poor to afford beautiful crafts — exemplify her commitment to Native women’s art and ways of life both in her own work and also as a founding member of the Aboriginal Arts Council of Alberta.

She creates heirlooms and ceremonial pieces, reviving crafts from the turn of the 20th century, a time Kootenay refers to as the “Renaissance period” of Métis and Cree beadwork. Some of them are inspired by the floral patterns of her Cree Métis grandmother, and the geometric designs are often influenced by her husband, Elder Camille Joseph Kootenay, in the style of his Stoney/Nakoda ancestors.

Kootenay’s works are never merely decorative; each piece is like a thread that unravels layers of meaning. Her two Tipi Bags, We Are Rising — #NoDAPL — Wet’Suwet’en Territory, for example, depict television sign-off screens, one featuring thunderbirds, which are an important Indigenous North American spiritual symbol reaching as far back as petroglyphs.

“[Thunderbirds] are transformational,” says Kootenay. “They are the power and source of electricity in the lightning…” In the 1970s, as her rural television screen flickered, she imagined that thunderbirds were causing the disturbance. “They are playing in that force field,” she explains. But thunderbirds are not to be toyed with. “They are very strong and you have to abide by them if you take the thunderbird path.”

In Kootenay’s worldview, even daily events can point to broader historical and spiritual truths. Soon after she and Symington were shortlisted for the 2021 Eldon & Anne Foote Visual Arts Prize, an award established with support from Edmonton Community Foundation and in partnership with Edmonton Arts Council and CARFAC Alberta, Kootenay witnessed a black crow rising out of a robin’s nest.

“It was a terrible sight,” Kootenay says, but remembers that a few days later, the fledgling robin came running. “He starts pecking at my toes, then jumps on my back and is crawling on my head. How often does that happen? The robin was a confirmation to me that the promise that we have offered to others through our artwork, was also going to be bestowed upon me, that the dark time I experienced would come to a close, and my health and happiness would be restored.” she recalls. “I felt that the little robin was giving me a message — a confirmation of hope, and the acknowledgment of a mission fulfilled.”

This story comes from the Winter 2021 edition of Legacy in Action. Browse the full magazine here.