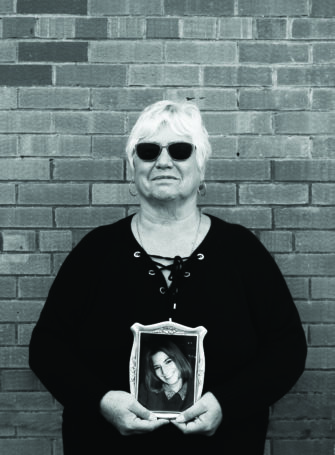

Kathy King is an ordinary mom doing extraordinary work in honour of her daughter

Even though Kathy King has been through life’s blackest moments, she still manages to find light within all that darkness.

King is the founder of Cara’s Friendship Fund, an endowment she set up with Edmonton Community Foundation in honour of her daughter, who was murdered in 1997. The fund is designed to help people vulnerable to sexual exploitation and living with mental illness.

“I’ve always wanted to be a philanthropist, but I’m a very ‘small p’ philanthropist because I’m not independently wealthy,” says the 70-year-old retired social worker. “I’ve got the spirit, but I don’t have the money.”

One of the groups that benefits from Cara’s Friendship Fund is the Centre to End All Sexual Exploitation, an Edmonton organization that works on awareness, prevention and healing. Through public education, bursaries, counselling and other means, CEASE provides a pathway for people to escape sexual exploitation and poverty. King’s connection to these issues is derived from the struggles of her late daughter. Cara suffered from developmental delays, mental illness and addiction issues, which led to her disappearing from the streets of Edmonton when she was 22 years old.

“I felt very helpless as a parent when my daughter was struggling with all her challenges,” King says. “It is extremely sad to be unable to provide shelter for your own child. I was trying to get agencies to take some responsibility for her, but people like Cara can really fall through the cracks.”

Despite Cara’s body being found in a farmer’s field more than 20 years ago, no one has been charged with her murder. King has been telling Cara’s story since then, pushing for changes in policing and government policy. Recently, at a silent auction, she bought the use of a digital billboard within the city of Edmonton, and for a month in August and early September she used that billboard to create awareness about a website she created as a result of Cara’s disappearance and death.

Sadly, Cara’s case isn’t atypical. Hundreds of sexually exploited people go missing every year in Canada, many of them Indigenous women. The Canadian government launched the National Inquiry Into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls on September 1, 2016, the 19th anniversary of the day Cara’s body was found. The inquiry has heard from more than 750 witnesses, including King, at hearings in more than 11 communities. Although the inquiry has been fraught with controversy and criticism, King draws comfort and hope from the fact that families had this forum to tell stories of their missing and murdered relatives.

“There’s so much stigma around sexual exploitation and mental illness. People tend to blame the exploited as having made their own choice,” she says. “One of the things, reflecting on the events of my life, that came out very strongly, was that consumers of sexual exploitation need to be held accountable for their actions.”

While her endowment can provide funding to groups helping people in poverty and who are homeless, King’s strong feelings about helping the sexually exploited play a key role in her decision

on what to support.

Working with people like King, who set up funds to help vulnerable people, is part of Edmonton Community Foundation’s mandate, says Noel Xavier, a donor advisor at ECF. “Issues around vulnerable people are a part of our society, unfortunately, and I think it’s something that needs to be addressed,” he says. “There is a certain stigma around this, which I think is wrong. I don’t think society needs to be fearful of having those conversations and one of the ways ECF can start combatting that is to work with families like Kathy’s to say, ‘This is something we need to address

in our community.’ ”

Of the more than 1,000 funds that ECF helps develop and administer, most are similar to Cara’s Friendship Fund — endowments developed by private citizens of modest means. “Most people think endowment funds are things that only millionaires can start, but the vast majority of our donors are ordinary Edmontonians doing extraordinary things,” says Xavier. “They are people like Kathy, who come to us and say, ‘I want to make this difference, I think I can do it in this way and these are the resources I have,’ and that’s enough to start.”