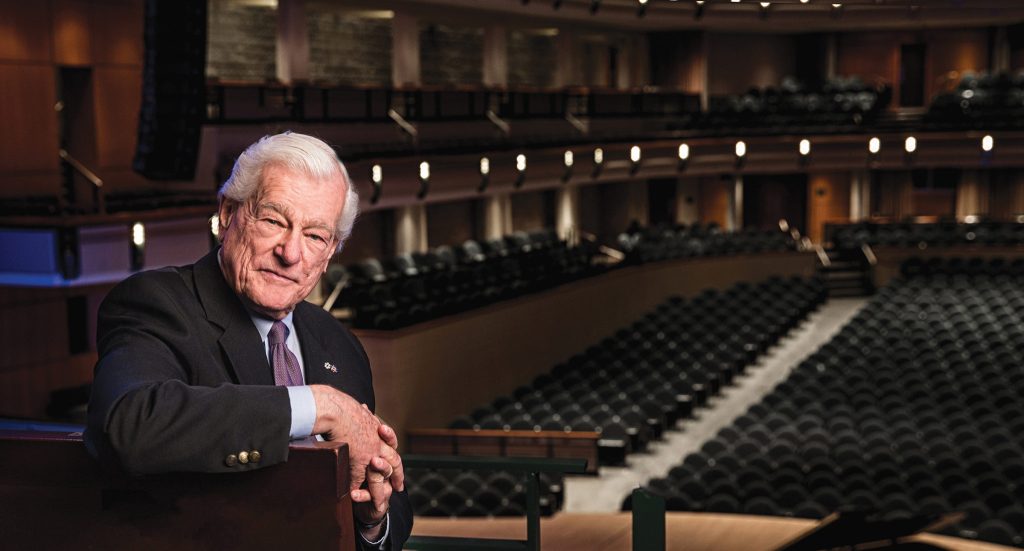

Not many Edmontonians have had the honour of getting a street named after them. But it’s a testament to Tommy Banks’ long and varied career – as a world-renowned jazz pianist, composer, producer, radio and TV host, and senator – that being the namesake of Tommy Banks Way, in Old Strathcona, might not even crack the top 10 items on his resum.

Now, Banks, 79, is turning his attention to the state of his fellow performing artists. Specifically, the state of their wallets. According to the Canada Council for the Arts, the average artist earns around $23,000 per year – 37 per cent less than the average Canadian. The Tommy Banks Performing Artists Fund, held by Edmonton Community Foundation (ECF), aims to correct that imbalance by providing financial assistance to local artists who might otherwise move to larger cities, as well as housing assistance for those whose financially precarious career choice has left them unable to, as he puts it, “retire with dignity.”

Michael Hingston: Your career has taken you into many different worlds, from music to television to federal politics. Growing up in Alberta in the ’30s and ’40s, were you interested in those things from an early age?

Tommy Banks: Yeah. I was a war baby, so when there’s a war on, you’re interested in politics because you’re hearing about it every day. And I was always interested in music, because my family was very musically oriented. There was always a lot of music going on in our house.

MH: By age 14, you were already a professional jazz pianist. What were those early gigs like?

TB: You can imagine a 14-year-old kid being on the road with a band. It’s enormous fun, and a wonderful learning experience. The only disadvantage was that whereas everybody else in the band took their [own] instruments, I had to play on whatever piano we found at whatever hall we were playing in – and some of them were pretty awful. Everybody in the band was a lot older and more experienced than I was. It was a very steep learning curve.

MH: Decades later, you led a jazz quintet at Expo ’67, and were the musical director of ceremonies for Edmonton’s Commonwealth Games and Calgary’s Winter Olympics. What goes into those kinds of large-scale productions that the average person might not realize?

TB: A lot of money, for a start. Because if you’re going to do things on the world stage, they have to be done at a level that will bring pride to the country. And the budgets for those things, fortunately, are always quite substantial.

In the case of the Olympics in Calgary, we started in 1987 and recorded over a span of about eight months. There was an enormous amount of music to be recorded: All of the music for the opening and closing ceremonies, for the medal ceremonies, and [for] several other events – all of which had to be built from scratch. That involved the talents of a large number of Canadian composers, orchestrators, arrangers, and, of course, musicians. The process took, in total, very nearly a year of our noses to the grindstone.

MH: You also hosted radio and TV shows for the CBC, and did your share of acting for the big and small screens. Was that a difficult transition?

TB: All of those things were a learning curve. You can’t go to school and learn how to be a television host – you probably can now, but you couldn’t then. And I appeared in films, in speaking roles, but I would never claim to be an actor.

MH: In 2000, Prime Minister Jean Chrtien invited you to join the Senate. Does that phone call come out of the blue?

TB: It was a complete surprise. And it was, at least in those days, to most of my colleagues. The Senate is usually comprised of about 25 to 30 per cent people who used to be politicians at some level. But the others were not. And most of them, like I, were completely surprised when we got the call. I leapt at the chance, because it was a chance to do something new and different, and to contribute to the country. It seemed like an exciting prospect, so I said yes immediately.

MH: The Tommy Banks Performing Artists Fund will provide affordable housing and financial assistance to retired performing artists. What was its inspiration?

TB: I have friends in the performing arts – dancers, actors, musicians, playwrights – who are not able to retire in the dignified circumstances to which they are entitled. So I wanted to find a way to change that, so that they can retire with dignity, and in better circumstances than they otherwise would. None of the money has been spent, because we’re still looking at how exactly to achieve those ends. It may not be, in the example of the movie Quartet, a specific building where performing artists can retire. That probably is not the answer for us here. But we’re looking at ways in which to do that, and we’re being very careful about it.

MH: The fund will encourage artists to stay and practise their craft in Edmonton. Where do these artists otherwise go?

TB: There are obvious magnets for performing artists: Hollywood, New York, Toronto, and to some extent Vancouver. We would like to make it easier for people to stay here – or to stay here long enough to develop their talent well enough that they can do well in those other places.

MH: Do you think people who choose careers in the arts are unusually susceptible to retiring without the money they will need?

TB: Yes. Some of us are lucky enough to have taken the necessary precautions, and we’re okay. But many performing artists – dancers, musicians, actors, singers – live in a world in which retiring with dignity is not always easy to do. Performing artists are rewarded very efficiently, shall we say. They do what they do because they want to do it, despite all of the other considerations, including economic ones.

MH: What would you say to people who are skeptical of this idea – who think artists are foolish for pursuing a career so financially unstable?

TB: Everybody knows that if you’re going to be a singer or a dancer or an actor, the likelihood of having a secure long-term job is very remote. But that is not foolish. That is the reason that we have great art, and great performers. That is pursuing one’s dreams. And that’s what everyone should always do.

A great lawyer, or a great doctor, or a great plumber are in professions in which it is relatively easy to retire in dignity, unless you’re really stupid. But for performing artists, it’s much harder to do that. They give us everything they’ve got, and then one day the phone isn’t ringing anymore. Their career has ended. And they haven’t been able to make, or have failed to make, provisions properly.

MH: Today, you seem to have accomplished about as much as one person could hope to do. What are you motivated by now?

TB: Playing music